Le film “War Sailor”, du cinéaste norvégien Gunnar Vikene, était projeté en compétition officielle à Camerimage.

En 1938, aux prémices de la guerre, Alfred, père de famille et ouvrier sur un chantier naval se laisse convaincre par son meilleur ami de l’accompagner en mer pour une mission de dix-huit mois. Mais, avec des dizaines de milliers de marins civils norvégiens, Alfred, Sigbjørn et leur nouvel équipage sont bientôt réquisitionnés pour soutenir l’effort de guerre anglais. Sans armes ni commandement, sous un statut indéfini, les deux amis sont déchirés entre leur honneur de marins et la promesse, faite à la famille d’Alfred, de rentrer à temps et en vie à Bergen.

En parallèle, celle-ci tente de continuer une vie normale, avec l’espoir du retour prochain d’Alfred. Ce n’est pas un film de guerre classique qui nous est présenté ici, mais plutôt une histoire de civils, essayant de vivre avec la guerre, puis d’en dépasser les conséquences et le traumatisme.

Interview avec le directeur de la photographie Sturla Brandth Grøvlen (“Béliers” 2015, “Victoria” 2015, “Drunk” 2020, “Wendy” 2020, “War Sailor” 2022).

Vous avez commencé par étudier l’histoire du cinéma, puis la direction de la photographie. Vous souvenez-vous à quel moment vous avez choisi cette voie ?

Mon intérêt pour le cinéma a commencé très jeune. Mais à ce moment-là, je ne connaissais que le métier de réalisateur, donc j’imaginais que je ferais celui-là. Après le lycée, j’ai commencé à étudier l’histoire du cinéma à l’université de Lillehammer en Norvège.

La Norwegian Film School était située au même endroit et je suis devenu ami avec des étudiants qui y allaient. A travers eux, j’ai découvert les autres métiers qui contribuent à fabriquer un film, comme ceux d’ingénieur du son et de chef opérateur. Je me suis intéressé de plus en plus à la photo, et à partir de là, j’étais sur le chemin qui me menait vers le métier de directeur de la photographie.

Mais étant musicien, j’étais aussi très intéressé par le sound design et l’ingéniérie du son. Alors j’ai beaucoup étudié. J’ai été un an dans une école de cinéma au Danemark. Puis je suis allé en école d’art. J’ai travaillé comme deuxième assistant caméra sur un tournage en parallèle de mes études. Et finalement je me suis inscrit en école de cinéma dans la section Image, parce que j’avais pris conscience que l’apport créatif du chef opérateur sur un plateau, était celui qui m’intéressait le plus. J’ai commencé l’école de cinéma à 27 ans, et je l’ai finie à 31 ans.. J’ai pris mon temps !

Vous avez choisi pour ce film des optiques vintages Bausch & Lomb Super Baltar, et un zoom K35, montés sur une Arri Alexa Mini.

Avez-vous effectué des comparaisons avec d’autres configurations ?

J’aime beaucoup les Super Baltar car elles ont une douceur et une texture très spéciales. Chaque optique a une personnalité différente, ce qui ajoute un élément de surprise. Je trouve qu’il y a une sorte d’énergie créative dans le fait de ne pas tout contrôler. Cela me manque de tourner en argentique, car il y a une certaine place laissée au hasard. Il y a l’exposition, puis le développement et le scan. Bien-sûr je ne tiens pas à ce que tout soit le fruit du hasard, mais j’aime l’idée de laisser de l’espace à un accident poétique, auquel on ne s’attendait pas. Je pense que mon attrait pour ces optiques vient de là. Chaque fois que je change de focale, il y a une petite surprise qui m’inspire d’une façon différente.

Cependant, pour “War Sailor”, je pensais choisir une autre série. Car lors de mes précédents films, les Super Baltar étaient aussi un challenge. Il y a eu des moments où je devais beaucoup les retravailler en post-production, et je pense que j’en étais un peu fatigué. Donc j’ai voulu aller dans une autre direction. Nous avons fait quelques tests, et… Gunnar est tombé amoureux du look de ces optiques !

L’autre problème que je rencontrais était que la série que j’utilisais était recarrossée de façon assez lourde, et avec une limite de point qui ne me convenait pas. J’ai eu la chance de trouver une série (la seule en Europe) qui avait un recarrossage différent, avec un close focus qui me permettait plus de proximité avec les acteurs. Elles étaient plus versatiles et beaucoup plus compactes. Le fait de trouver cette série m’a aussi aidé dans ma décision.

Quelle fut votre collaboration avec les équipes sur toute la chaîne du workflow, de la prépa à la post-production ? Avez-vous travaillé avec l’étalonneur en préparation ?

J’ai commencé une nouvelle collaboration avec un jeune étalonneur, vraiment pointu en color science. Je l’ai choisi car il avait publié des articles sur la façon d’obtenir un rendu proche de l’argentique à partir d’une image numérique. Cela m’a semblé adapté pour un drame historique.

A l’origine, je voulais tourner en argentique, mais nous n’avions pas le budget nécessaire. J’ai donc voulu engager un expert, qui irait plus loin que ce que mes connaissances me permettaient d’obtenir, pour créer une image numérique plus organique, se rapprochant du 35mm.

Nous avons fait pas mal de tests : avec l’Alexa mini et en 35mm, scanné et projeté, et il a réussi à les faire matcher. Je ne connaîs pas vraiment le procédé technique, mais il a créé une LUT très juste. Et nous avons continué dans cette direction à l’étalonnage. Il y avait une seule LUT pour tout le film, à part pour la scène finale, pour laquelle nous avons créé une LUT plus douce et moins saturée.

Venant de Norvège et du Danemark, comment avez-vous abordé la lumière exotique de Malte, et la partie à « Singapour » ? Avez-vous utilisé un équipement différent (pour des raisons esthétiques ou de production) ?

On a un peu galéré avec Malte parce que certaines scènes devaient se passer en mer du Nord. Mais la température est bien meilleure en mer Méditerranée. Et les conditions de travail étaient beaucoup plus sûres. Donc on a fait avec ! Pour la partie à Singapour (que nous avons aussi tournée à Malte), nous étions principalement en intérieurs, donc nous pouvions contrôler l’éclairage. Nous avons utilisé un fond vert pour créer la jungle en découverte. Mais sinon, je ne pense pas que nous ayons eu une approche très différente de celle du reste du film.

Comment vous êtes-vous préparé pour New York dans les années 40 ?

C’est un grand coup de chapeau pour le département déco ! Ils étaient vraiment, vraiment talentueux et ont beaucoup travaillé. Ce n’est pas facile de créer un décor où l’on tourne essentiellement à 360 degrés, de le faire ressembler à une époque précise, et à New York. On a tourné ces séquences sur le port de Hambourg. Et je pense que cela fonctionne bien. Nous n’avons pas recouru à de nombreux VFX, seulement la skyline sur quelques plans.

J’avais des références photographiques en noir et blanc. Et je voulais des noirs profonds et des lumières très dures, pour créer ce look Film Noir que j’associe aux années 40 à New York.

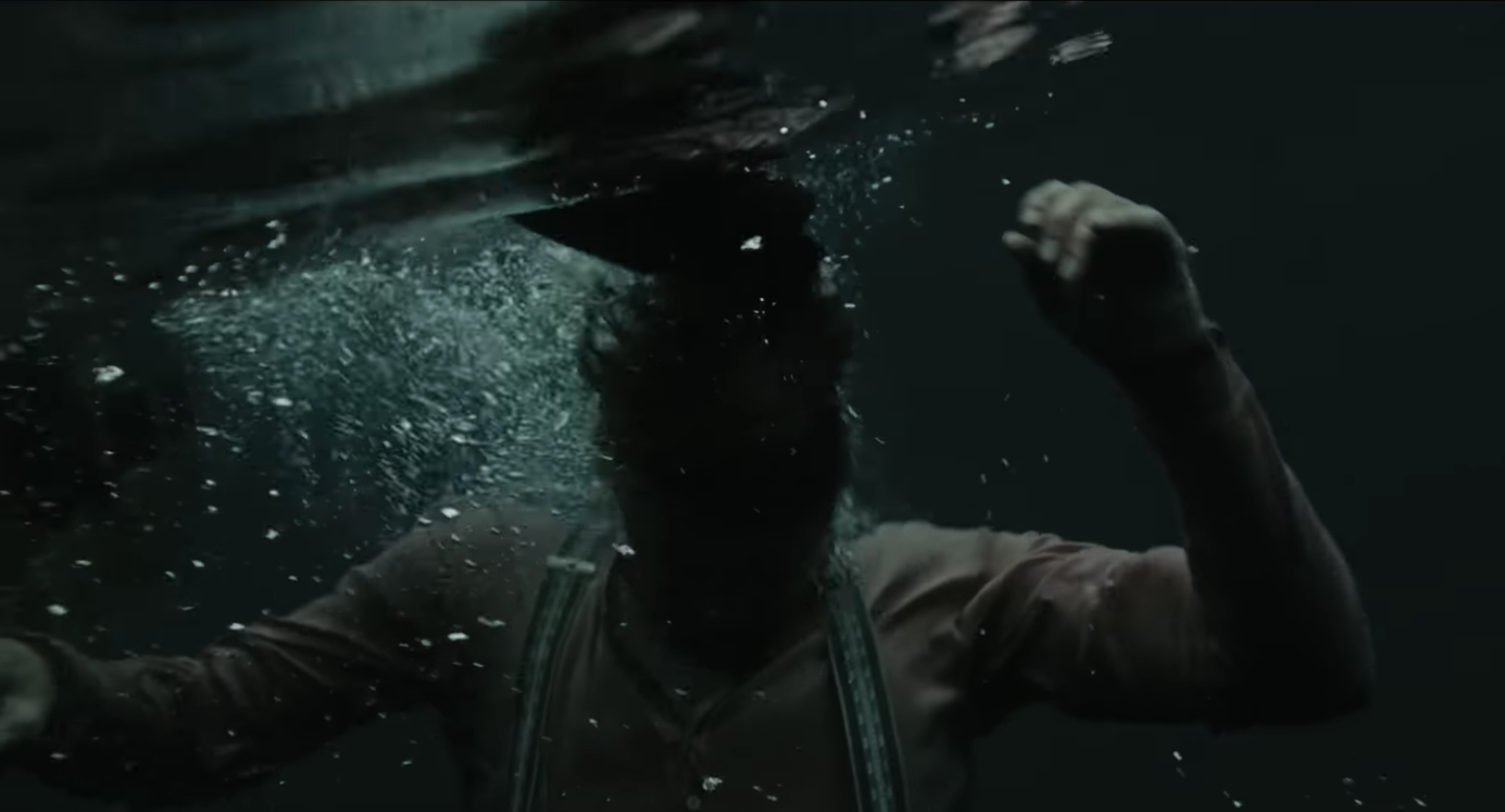

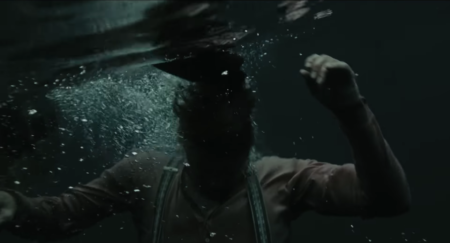

Les séquences sous-marines ont été tournées à Malte. Vous avez utilisé une grue équipée d’une tête télécommandée étanche. Le radeau était au large. Vous aviez un vaisseau-mère qui, avec le rivage, a dû être gommé numériquement pour le plan à 360° autour du radeau. Vous avez aussi dit au Q&A que filmer sous l’eau était avant tout chose : « chronophage ». Sur ces séquences avez-vous opéré vous-même ?

Oui, j’opérais l’Hydrahead. Je préfère cadrer moi-même, dans une certaine mesure. Mais cette fois j’ai aussi eu la chance d’avoir un jeune plongeur de sécurité (nous en avions beaucoup autour du radeau), qui nageait dans l’eau comme un poisson et qui était très intéressé par la cinématographie. Alors je lui ai demandé de faire un des plans. C’est lorsque Alfred nage vers le garçon et le ramène au radeau. C’était un plan assez compliqué à tourner car il fallait avoir le garçon au premier plan et ensuite nager derrière eux. J’ai laissé ça à quelqu’un de plus habile que moi dans l’eau.

Nous avons passé deux semaines à filmer les scènes aquatiques. Nous avions un grand fond vert que nous utilisions pour intégrer des éléments ou pour simuler l’ombre du bateau. Nous étions sur une barge, et près de la jetée, nous avions ce fond vert. Puis en post-production, ils ont créé le bateau et les dommages. Nous avions fait des calculs. Certains ne correspondaient pas exactement. La taille et la position des objets ont dû être réajustées. Je préfère définitivement filmer de vrais éléments. Comme le sous-marin : c’était un vrai sous-marin.

Avec un budget de 10 Millions et 60 jours de tournage, le film est un projet européen confortable, et pourtant très léger par rapport à la dimension épique de certaines séquences, et aux époques et lieux traversés par les personnages.

Dans quelle mesure les effets spéciaux d’aujourd’hui ont permis quelque chose qui aurait été impossible auparavant ? (Sur « Les Dents de la mer », par exemple, certaines prises étaient inutilisables car des bateaux traversaient le cadre. Et le tournage de « Titanic » a dépassé son plan de travail de cent trente huit jours).

Par ailleurs, vous avez participé au montage du film et à l’intégration des VFX. Parfois, les directeurs de la photographie ne sont pas clairement invités lors de ces étapes de travail, qu’en pensez-vous ?

Peut-être parce que j’ai obtenu mon diplôme il y a 10 ans, mais à l’époque nous n’avions aucune formation en VFX. Et nous n’avons pas rencontré de créateurs d’effets spéciaux. Dans mes films jusqu’à présent, il y avait peu d’effets visuels, et ils étaient généralement combinés avec des éléments physiques (comme sur « Wendy » de Benh Zeitlin – 2020). Pour moi c’était une nouvelle expérience.

J’ai été impressionné par ce qu’ils étaient capables de faire, en particulier avec l’eau et la simulation de l’eau. On m’avait toujours dit que de mettre des éléments dans l’eau, et de les faire interagir avec de l’eau en mouvement, était la chose la plus difficile à faire. Par exemple, pendant la scène où le navire est brisé et qu’ils essaient de sauver des marins de la noyade, presque toute l’eau est une simulation. J’ai été bluffé. Je suis sûr que chaque jour il y a une nouvelle avancée dans les effets visuels. Mais vous avez raison : il est rare que le directeur de la photographie soit invité dans ce processus. J’ai eu la chance de l’être.

Sur certains types de projets, le superviseur des effets visuels est un collaborateur aussi important pour un réalisateur qu’un directeur de la photographie. Et il doit être traité comme tel. Il y a du goût en jeu. Il y a du talent en jeu. Il y a de la personnalité. Toutes les choses qu’un chef opérateur doit aligner avec les intentions du réalisateur, elles ont aussi un sens pour le superviseur des effets visuels. Si le réalisateur et son superviseur VFX ne se comprennent pas, le film va en souffrir.

Et bien sûr, le directeur de la photographie y est sensible, parce que les effets spéciaux créent des images et que vous voulez avoir votre mot à dire. Sur « War Sailor », nous faisions un point chaque semaine sur les plans en cours. A un moment, le réalisateur est tombé malade, et j’ai pris temporairement le relais pour travailler avec l’équipe VFX. J’ai énormément appris de cette expérience. Je pense que c’est super important que nous soyons invités davantage. C’est une collaboration, comme l’étalonnage.

Vous avez dit au Q&A que vous cadrez habituellement vous-même, étant « incapable de communiquer clairement avec un cadreur ». Vous semblez aimer jouer avec les acteurs, leur donnant ainsi qu’à vous-même, beaucoup de liberté.

Par exemple, le push-in sur le visage de Maggie au départ de son père semble très spontané. Je pense aussi à votre travail sur « Drunk» de Thomas Vinterberg. Avez-vous parfois l’impression que le cadreur est un acteur de plus sur le plateau ?

D’une certaine manière, oui. Ou en tout cas, j’ai l’impression que vous devez créer une performance authentique en tant que cadreur. Le public le sent si vous faites semblant. Vous avez le pouvoir de souligner les émotions. Parfois, vous pouvez même en faire trop. Pour moi c’est important de m’engager émotionnellement dans la scène, de comprendre les personnages, et de vraiment essayer de ressentir ce qu’ils ressentent. Cela peut sembler abstrait, mais ça compte plus pour moi que d’avoir une lumière parfaite. J’aime avoir la liberté de filmer à 360°. Ou si j’en ai envie, de faire une prise en contre-plongée. Je me donne cette liberté de m’immerger dans une scène, sans avoir à penser à ce que je vais faire.

Après “Béliers », votre travail a été remarqué sur « Victoria » de Sebastian Schipper. Ce long-métrage tourné en un plan séquence était un défi, tout comme « War Sailor » à sa manière. Que pensez-vous de la prise de risque ? Comme un choix de carrière ?

Hahaha. Je pense que j’ai toujours aimé me défier, ou me sortir de ma zone de confort. Je suis quelqu’un qui pourrait facilement s’asseoir sur le canapé, boire une tasse de thé, regarder Netflix et rester là. Je suis plutôt introverti et timide. Mais au fil des années, j’ai essayé d’élargir mon horizon.

“Victoria” ne me faisait pas si peur, car cela ressemblait aussi à une étape dans mon développement personnel. En fait, quand j’ai fait “Victoria”, ce n’était pas un choix. C’était juste une opportunité intéressante. Et une fois qu’il était clair que j’allais le faire, alors c’était juste une réalité, une tâche à laquelle je devais faire face : foncer et terminer ce film du mieux que je le pouvais.

Cela se produit pour chaque projet dès que vous commencez à entrer dans l’histoire. C’est ce qui devient important, et vous essayez de la raconter selon votre propre sensibilité et votre propre goût. Et puis viennent bien sûr, tous les aspects techniques et logistiques. Ce ne sont que des obstacles que vous devez surmonter.

En réalité, la chose la plus importante est que j’ai une bonne connexion avec le réalisateur. Parce que faire un long métrage est tout simplement épuisant, et j’ai besoin d’une bonne collaboration, de travailler avec un bon ami. Nous devons être capables de parler de tout et d’être vulnérables, de passer une mauvaise journée et ensuite nous ressaisir. Une bonne équipe, c’est le meilleur point de départ pour faire un bon film.

« War Sailor » est le candidat norvégien aux Oscars cette année.

En plus : article de l’AFC

The movie “War Sailor”, by the Norwegian Gunnar Vikene, was screened in the official competition at Camerimage.

In 1938, at the beginning of the war, Alfred, a father of three and worker in a shipyard, was convinced by his best friend to accompany him to sea for an eighteen-month mission. But along with tens of thousands of Norwegian civilian sailors, Alfred, Sigbjørn, and their new crew are soon requisitioned to support the English war effort. Without weapons or command, under an indefinite status, the two friends are torn between their honor as sailors and the promise, made to Alfred’s family, to return in time and alive to Bergen.

In the meantime, the latter try to lead their daily lives, with the hope that Alfred will return soon. This is not a classic war movie that we are presented here, but rather a story of civilians attempting to live with war, then overcoming the consequences and the trauma from it.

Interview with the director of photography Sturla Brandth Grøvlen (“Rams” 2015, “Victoria” 2015, “Another round” 2020, “Wendy” 2020, “War Sailor” 2022)

You first studied cinema history then cinematography. Do you remember the moment when you chose this path ?

I started quite young having a very strong interest in cinema. But at that time, I thought the only job you could do was to be a director. So that was something I thought I wanted to do. After high school, I started studying film history at the university in Lillehammer, Norway.

At the same university, The Norwegian Film School is located, and I got to know some of its students. I realized the diversity of jobs that could contribute to the making of a film, like sound engineer and cinematographer. That’s partly where I understood that it could be interesting to go deeper into photography and cinematography, and from then on, I was on a path that was leading toward cinematography.

However, Being a musician, I was very interested in sound design and sound engineering. So I studied a lot. I did a one-year program at a film school in Denmark. Then I went to art school and got more and more into photography, and eventually applied to film school as a cinematographer. I had by then worked as a clapper loader in some films, besides my studies. And I realized that the cinematographer was the job on a film set, or the part of creating a film, that interested me the most. I started film school when I was 27, for four years, and finished at 31. I was kind of late in the game.

You chose to film with Bausch & Lomb Super Baltar vintage lenses and a zoom K 35, mounted on an Arri Alexa Mini camera.

Did you compare them to other combinations ?

Super Baltar are lenses I like a lot because they have a very specific texture and softness. Each lens has a different texture as well. It adds a surprising element. There is some sort of creative energy in not having control over everything. I sometimes miss shooting analog, because there’s a certain element of randomness in it. There is the exposure, and then it gets processed and then scanned. Of course, I don’t like it to be totally random. But I also like having some sort of poetic results, that you haven’t expected or can’t calculate beforehand. And I think this is why I like these lenses. Every time I put a different lens on the camera, there’s a small surprise that inspires me in a different way.

However, I thought that for “War Sailor” I would choose something else. Because during my previous films, the Super Baltar lenses were also a challenge. It’s not all good, it’s not all inspiring. There were times in post-production when you had to correct a lot, and I think I was a little bit exhausted by that, so I wanted to go a different path. We did some tests and… Gunnar just fell in love with their look. And I wasn’t too difficult to convince when he loved it, because I do too.

I had another problem with the lenses because they were rehoused, and the rehousing of the ones I used was a little bulky, and with a close focus that wasn’t to my liking. So I found a different set (there was only one in Europe) that had a different rehousing, with a close focus which made me be able to be closer to the actors. They were more versatile and more compact. Finding this particular set of lenses also helped me in making the decision.

What kind of collaboration did you have on the workflow from pre- to post-production ? Did you work with the colorist in pre-production?

Yes, I did. I started a new collaboration with a young colorist. The reason why I wanted to work with him was that he had published some articles on the matching of digital to film. He is really nerdy about color science, trying to create a digital image that would look more like film. And I thought that was right for a historical drama.

Initially, I wanted to shoot on film, but there wasn’t a budget for it. So my idea was that I would hire an expert, who would go further than I could with my knowledge, into trying to make a digital image look more organic, like 35mm. We did a lot of testing: shot with the Alexa mini and in 35mm, printed and projected, and he made them match. I’m not quite sure what the technical process was, but he created a very accurate LUT.

Then we continued building on that during color grading. There was one LUT for the entire movie. Except for the end scene, where we created a softer and less saturated LUT.

Coming from Norway and Denmark, how did you approach the exotic light of Malta, the « Singapour » part ? Did you use a different equipment (for aesthetic or production reasons)?

Not so much in terms of lights. I mean, we struggled a little bit with Malta because some of the scenes were supposed to be taking place in the Northern sea, and in the Mediterranean sea, the light is quite different… But the temperature is much better. And the working conditions are much safer. So it was what we had, and what we could work with. For the Singapore part (which we also shot in Malta), we were mostly in interiors, and we could control the lighting. We had to use a green screen to create a jungle afterward but otherwise, I don’t think we had a very different approach from the rest of the film.

How did you prepare for New York in the 40’s ?

That’s a big shoulder clap to the art department. They were really, really talented and gave us a lot to work with. It’s not easy to create a set where we basically shoot 360, make it look like a period piece, and furthermore set in New York. We shot this in Hamburg, at the harbor. It was a big set that they had to create, and I think it worked out pretty well. We didn’t do too much CGI, only the skyline in a couple of shots.

I had photographic references, black-and-white stills of New York harbor environments. And I wanted deep blacks and very hard lights, to create this almost Film Noir look, which is what I associate with the 40s in New York.

The underwater (or for the most part of them the between-air-and-water) sequences were shot in Malta. You used a crane equipped with a waterproof remote head. The raft was offshore. You had a mothership that had to be digitally removed as long as the shore itself for the 360° shot around the raft.

You also said at the Q&A that: filming underwater was, first thing: « time consuming ». On those sequences did you operate yourself ?

Yes, I operated the Hydrahead. I like operating to a certain extent, but I was actually also lucky to have a young safety diver (we had a lot of them around the raft) who was very interested in cinematography. So I asked him to do one of the shots, because he could swim in the water, like a fish. It was the shot when Alfred swims over to the boy and drags him back to the raft. It was a fairly complicated shot because you had to have the boy in the foreground and then swim after them. I left that to someone who is more used to being in the water and operating with a splash bag.

We spent two weeks filming the water scenes. We had a big cut-out green screen that we used to integrate assets or to fake the shadow of a boat. We were on the barge, and by the pier, we had a big green screen set. Then in post-production, they created the ship and the damages. We had done calculations. Some didn’t match exactly. The size and position of the objects had to be readjusted in post. I definitely prefer shooting real props. Like the submarine, it was a real prop.

With a 10 Million budget and 60 days of shooting, the movie is a comfortable European project and still a very light one compared to the epic dimension of some sequences, and the time periods and places the characters travel through. To what extent have today’s CGI possibilities allowed something that may have been impossible before ? (On “Jaws”, for example, some takes were useless because boats were crossing the frame. “Titanic” went one hundred and thirty-eight days over schedule)

Also, you participated in the editing and CGI integration. Sometimes the DoPs are not that openly invited during those work stages, how do you feel about that ?

It is maybe because I graduated 10 years ago, but at the time we didn’t have any training in CGI, and we didn’t really have met any visual effects artists. In my films so far, there have been very few visual effects, and they were generally combined with physical elements (like on “Wendy” by Benh Zeitlin – 2020). So for me, this was a new experience.

I have been quite impressed by what they can do, especially with water and water simulation. I had always been told that putting elements in water, and having them interact with moving water, was the most difficult thing to do. And I was amazed by what they actually were able to do. For example, during the scene when the ship is broken and they are trying to save some sailors from drowning and floating out, almost all of that water is a simulation. Every day I’m sure, there’s a new advance in visual effects. But you’re right: it’s rare that the cinematographer is invited in this process. I was lucky to be.

On certain kinds of projects, the visual effects supervisor is as important a collaborator to a director as a cinematographer is, and should be treated as such. There is taste involved. There’s talent. There’s personality. All those things that a DoP aligns with the intentions of the director, they also have a sense for the visual effects supervisor. It must not be underestimated. If the director and his visual effects supervisor are not in sync, the project might suffer from it. And of course, the cinematographer feels that his or her work is suffering because visual effects create images and you want to have a say in it.

On “War Sailor”, we had weekly updates for work-in-progress shots. And at one point, the director got sick, and I took over for a little bit, to work with the visual effects crew. So I learned a lot from this experience. I think it’s super important that we are invited in more. It is a collaboration, like color grading.

You said at the Q&A that you usually operate yourself being « unable to clearly communicate with a camera operator ». You seem also to enjoy playing with the actors, giving them and yourself a lot of freedom. For example, the push-in on Maggie’s face at the departure of her father seems quite spontaneous. I’m also thinking about your work on Thomas Vinterberg’s « Another round ». Do you sometimes have the feeling that the camera operator is one more actor on the set ?

In a way, yes, maybe I do feel like that. At least, I feel like you have to create an authentic performance as a camera operator. The audience is sensitive to when you’re faking. You can enhance emotions. Sometimes, you can even do too much, you can over-enhance. I feel like when I do my best operating is when I can engage emotionally with the scene and understand the characters, and really try to feel what they’re feeling.

It may sound abstract, but it’s more important to me than having the perfect lighting. I like to have the freedom to shoot 360, or if I get the urge to do a low-angle shot, I want to be able to do so at the moment. It’s like having that freedom of really immersing myself in a scene, in a way that I don’t have to think about what I’m going to do, but I just act on emotion.

After “Rams”, your work was noticed on Sebastian Schipper’s “Victoria”. This one-sequence feature movie was obviously a challenge, and so is “War Sailor” in its own way.

How do you feel about taking risks ? Career-wise ?

Ha ha ha. I think I’ve always been very interested in challenging myself, or maybe it’s more likely getting out of my comfort zone. I think I’m a person that could easily just sit on the couch, drink a cup of tea, watch Netflix, and just stay there. I’m quite introverted and quite shy. But over the years I’ve been trying to open and broaden my horizon. I think I’m trying to make a conscious decision about those kinds of projects that challenges my personality.

Victoria felt not so scary, as it felt like a step in my own personal development as well. Actually, when I did Victoria, it wasn’t a choice, it just felt like an interesting opportunity. And once it was clear that I was going to do it, then it was just a reality, a task I had to deal with: going full speed ahead and trying to complete that film as best as I could.

That happens in every project once you start going into the story. That’s what becomes important and you try to solve it, according to your own sensibilities and your own taste. And then come, of course, all the technical and logistical aspects. They just are obstacles that you have to overcome. The most important thing is that I have a good connection with the director because going through the process of making a feature film is just exhausting, and I need a good collaboration, like a good friend to work with. We have to be able to talk about everything and be vulnerable, have a bad day and then pick each other up. That feeling of a good team is a good foundation for making a good film.

-

Partager l'article