Si vous avez fait un tour au MicroSalon cette année, vous avez peut-être découvert sur le stand de TSF un étrange système optique : le Stemirax, qui permet de créer des superpositions d’images à la prise de vues. Le concepteur de cet objet, Théo Fauger, réalisateur et chef opérateur, est un passionné des débuts du cinéma et collectionneur de jouets optiques anciens. Ce qu’il aime, c’est la possibilité de créer des effets sans recours à la post-production, dès le tournage.

Sa passion pour les inventions liées aux origines du cinéma le conduit à souvent explorer les forums d’amateurs. Il découvre ainsi le Stereax, un système photo argentique datant des années 1950. Grâce à un jeu de quatre miroirs le Stereax permet de prendre simultanément deux images d’une même scène, avec deux points de vue légèrement décalés, afin de recréer ensuite une image en relief.

Il crée alors une alerte sur Ebay, et un an plus tard acquiert un modèle venu de Nouvelle Zélande pour la modique somme de 20 dollars. Il le monte sur le cerclage d’un filtre polarisant afin de pouvoir le fixer facilement sur n’importe quel objectif photo, tout en permettant de le faire pivoter autour de l’axe optique.

Cependant, il trouve l’objet limité et le relègue sur une étagère en attendant de trouver comment l’utiliser de façon plus créative.

Il se rend néanmoins compte qu’il peut détourner le Stereax de son utilisation initiale pour créer des surimpressions.

Quelque temps plus tard, un ami pianiste lui donne carte blanche pour lui réaliser un court-métrage doublé d’un clip : Les scintillements. Le projet est ambitieux et dispose d’un financement confortable.

Théo souhaite opposer deux univers : la ville agressive et la montagne paisible. Il réfléchit alors à comment filmer l’épilepsie, comment restituer la sensation que la lumière inonde le personnage.

Lui vient l’idée de créer des surimpressions. Il repense alors au Stereax et cherche à en adapter le principe pour cette fois-ci obtenir des superpositions d’images à la prise de vues, avec la possibilité de régler les réflexions.

Il cherche alors à rencontrer des ingénieurs pour la fabrication, jusqu’à se tourner vers un oncle qui possède une usine en Tunisie qui fabrique des pièces pour des sièges d’avion. Un domaine certes bien éloigné de l’optique, mais cela lui permettrait d’accéder à des outils spécialisés.

Son oncle lui présente alors un jeune ingénieur qui travaille avec lui et qui, par plaisir de relever le défi technique, accepte de se pencher sur la question.

Le cahier des charges présente plusieurs enjeux, liés à une utilisation cinéma : s’adapter aux normes dimensionnelles d’accessoirisation cinématographiques, et permettre une motorisation des miroirs afin de contrôler plus facilement et précisément les effets, donc de laisser une plus grande liberté créative. Afin de pouvoir utiliser le système avec des optiques cinéma, qui ont un diamètre bien plus élevé que les optiques photo, il faut agrandir l’ensemble. Cependant le diamètre ne doit pas dépasser une certaine dimension afin de permettre aux miroirs de tourner autour de l’axe optique, sachant que le système sera fixé sur tiges. Par ailleurs, afin que la ligne où les miroirs se rejoignent devant l’objectif reste invisible, il faut qu’elle soit le plus proche possible de la lentille, et le plus fine possible, et donc que les bords des miroirs soient précisément biseautés.

Autre difficulté: pour modifier l’angle des miroirs de façon mécanique (au moyen d’un moteur utilisé habituellement pour la mise au point par exemple), il s’agit de transformer un mouvement circulaire en un mouvement linéaire.

Après de nombreux échanges et tentatives, le prototype est enfin prêt. Malgré une livraison in-extremis, Théo le récupère juste à temps pour l’utiliser sur son tournage.

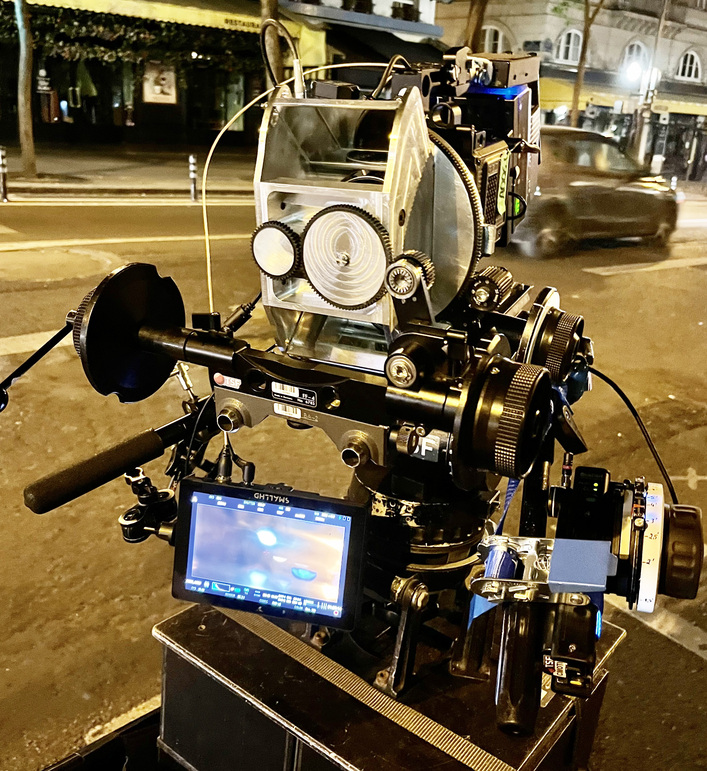

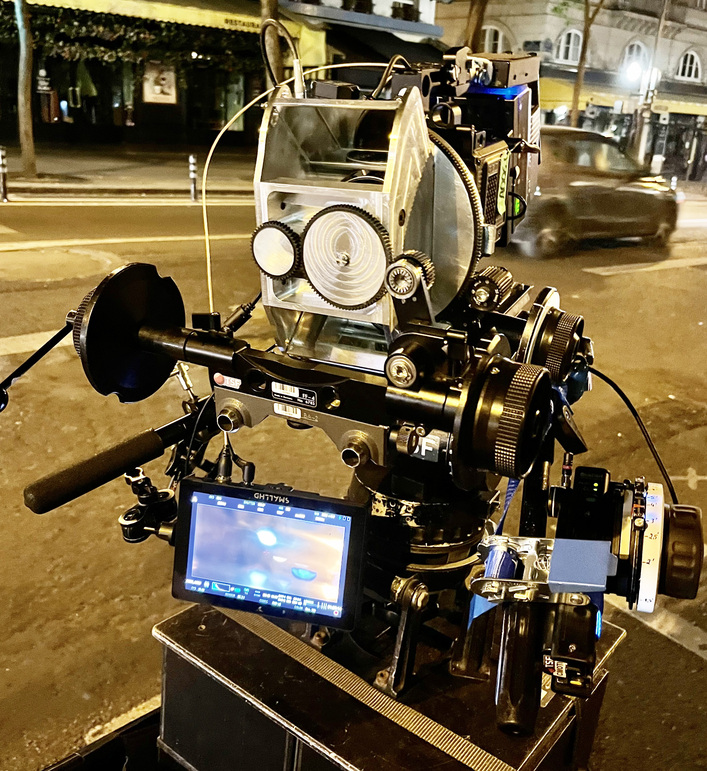

D’un point de vue pratique, le Stemirax peut facilement être monté sur des tiges de diamètre 19. L’angle des miroirs peut être contrôlé grâce à un follow focus, de même que la rotation du système autour de l’axe optique.

Le Stemirax en configuration de tournage – Photo Théo Fauger

Contrairement au Stereax qui présentait une grosse déperdition de lumière, l’utilisation du Stemirax n’entraîne une perte de luminosité que d’1/3 de diaph environ, ce qui le rend utilisable aussi bien dans un intérieur sombre qu’en extérieur jour.

Il est compatible avec bon nombre d’optiques cinéma, tout en gardant à l’esprit qu’en deçà d’une certaine focale, l’angle de champ devient trop large et on peut voir le système ; il est donc préférable de recourir au moins à un 50mm.

Enfin, afin de ne pas sentir la jonction entre les miroirs centraux, il est recommandé de privilégier les grandes ouvertures.

Réaliser un effet sans recours à la post-production procure une certaine satisfaction, à l’instar des trucages de Méliès dont la simplicité n’enlevait rien à leur efficacité ni à leur magie. Par ailleurs, tout l’intérêt du Stemirax de pouvoir réaliser les superpositions dès la prise de vues réside dans la possibilité de mieux ajuster chaque image et contrôler leur interactions. Cela permet notamment de diriger les comédiens plus précisément, en fonction des effets obtenus.

Théo envisage déjà comment améliorer son invention pour stimuler davantage la créativité.

Les possibilités restent largement à explorer. Il serait notamment intéressant de pouvoir changer les miroirs, pour disposer d’une gamme d’éléments plus ou moins sombres, teintés de différentes couleurs, avec des textures apportant un flou plus ou moins prononcé… On pourrait ainsi superposer deux images d’un même objet avec un faible décalage mais un traitement différent.

Le Stemirax a fait l’objet d’un dépôt de brevet. Pour l’instant Théo préfère accompagner son utilisation sur les plateaux, notamment car il considère que son expérience lui permet d’atteindre plus efficacement le rendu souhaité. Il n’est pas exclu qu’une fabrication plus large soit lancée dans le futur.

-

ENGLISH VERSION

If you attended the MicroSalon this year, you might have come across a peculiar optical system at the TSF booth: the Stemirax, designed to create in-camera image overlays. Théo Fauger, the creator of this device, is a director and cinematographer who is passionate about the early days of cinema and collects antique optical toys. He loves creating effects without resorting to post-production, right from the moment of filming.

His passion for inventions related to the origins of cinema often led him to explore amateur forums. This is how he discovered the Stereax, a silver-halide photography system from the 1950s. With a set of four mirrors, the Stereax can simultaneously capture two images of the same scene from slightly offset viewpoints to recreate a 3D image later.

He then sets up an eBay alert and, a year later, acquires a model from New Zealand for the modest sum of $20. He mounts it on a polarizing filter ring to easily attach it to any camera lens, allowing it to rotate around the optical axis.

However, he finds the device limited and shelves it while waiting to figure out how to use it more creatively.

Nonetheless, he realizes he can repurpose the Stereax to create image overlays.

Some time later, a pianist friend gives him free rein to create a short film combined with a music video: The Flickerings. The project is ambitious and enjoys comfortable funding.

Théo wants to contrast two worlds: the aggressive city and the peaceful mountains. He then considers how to film epilepsy and convey the feeling of being flooded with light.

He comes up with the idea of creating image overlays. He reconsiders the Stereax and tries to adapt its principle to create in-camera image overlays, with adjustable reflections.

He then seeks engineers to help with manufacturing and eventually turns to an uncle who owns a factory in Tunisia that produces parts for airplane seats. Although this field is far removed from optics, it would grant him access to specialized tools.

His uncle introduces him to a young engineer working with him, who agrees to tackle the technical challenge for the sheer pleasure of it.

The project’s specifications present several challenges related to cinema use: adapting to standard cinematic accessory dimensions, allowing motorized mirror control for more accessible and precise effects management, and ensuring greater creative freedom. For example, the device needs to be enlarged to use the system with cinema lenses, which have a much larger diameter than photo lenses. However, the diameter must not exceed a specific size so that the mirrors can rotate around the optical axis, considering that the system will be mounted on rods. Furthermore, to keep the line where the mirrors meet in front of the lens invisible, it needs to be as close to the lens as possible, as thin as possible, and the mirror edges must be precisely beveled.

Another challenge: to mechanically adjust the mirror angles (using a motor typically employed for focusing, for example), a circular motion must be converted into a linear one.

After many exchanges and attempts, the prototype is finally ready. Despite a last-minute delivery, Théo receives it just in time to use it on his shoot.

In practical terms, the Stemirax can be easily mounted on 19mm diameter rods. The mirror angles can be controlled using a follow focus, as well as the system’s rotation around the optical axis.

Le Stemirax en configuration de tournage – Photo Théo Fauger

Stemirax in a shooting configuration – Photo by Théo Fauger

Unlike the Stereax, which suffered significant light loss, the Stemirax only causes around 1/3 stop of light loss, making it usable both in dark interiors and daylight exteriors.

It is compatible with many cinema lenses, keeping in mind that below a particular focal length, the field of view becomes too wide, and the system becomes visible; therefore, using at least a 50mm lens is preferable.

Moreover, to avoid seeing the junction between the central mirrors, it is recommended to use large apertures.

Achieving an effect without resorting to post-production brings satisfaction, reminiscent of Méliès’ tricks, whose simplicity did not diminish their effectiveness or magic. Additionally, the advantage of the Stemirax in creating image overlays during filming lies in the ability to better adjust each image and control their interactions. This allows for a more precise direction of actors based on the effects achieved.

Théo is already considering how to improve his invention to stimulate creativity further.

There are still many possibilities to explore. For example, it would be interesting to be able to change the mirrors, to have a range of lighter or darker elements, tinted in different colors, and with textures that create varying degrees of blur. This way, it would be possible to overlay two images of the same object with a slight offset but with different treatments.

The Stemirax is patent-pending. For now, Théo prefers to personally accompany its use on set, mainly because his experience allows him to achieve the desired results more effectively. However, a larger-scale production may be launched in the future.

-

Partager l'article