Walter Murch prépare un livre où il explore l’étrange pouvoir du Nombre d’Or sur notre façon de cadrer des images.

L’un des premiers séminaires du festival Camerimage 2022 était animé par le légendaire monteur Walter Murch (“Le Parrain” (1972), “Conversation Secrète” (1974), “Apocalypse Now” (1979) et bien d’autres).

Il a partagé ses réflexions sur le Nombre d’Or dans le cadrage cinématographique.

Une théorie intrigante sur la façon dont les directeurs de la photographie et les cameramen ont « naturellement » tendance à favoriser une position similaire d’un visage dans le cadre.

Un soir, alors qu’il regardait la télévision avec sa femme qui tricotait, Murch a décidé de tenter une expérience. Il a pris un brin de laine et l’a fixé horizontalement sur l’écran, à hauteur des yeux. Alors qu’ils continuaient à regarder, il a remarqué que les lignes de regard semblaient tomber systématiquement dans la même zone de l’écran.

Comme il est un peu mathématicien, il a décidé de prendre un mètre ruban et de mesurer la distance entre le bas de l’écran et le fil, puis entre le fil et le haut de l’écran. Lorsqu’il a divisé ces chiffres entre eux, il a obtenu un rapport qu’il a reconnu comme étant le Nombre d’Or (1,618 ou phi « ϕ »).

Le Nombre d’Or apparaît tout autour de nous dans la nature, des spirales trouvées dans les coquillages aux formes des galaxies, en passant par la spirale de notre propre ADN. Intrigué, il s’est demandé si ce rapport d’or apparaissait dans d’autres films et pourquoi il ne l’avait pas remarqué après presque soixante ans de montage de films.

Il a donc réalisé une vidéo de nombreuses photos de films montrant ce rapport et en a parlé à Francis Ford Coppola et à plusieurs de ses amis directeurs de la photographie (dont Vittorio Storaro et John Seale). Il leur a demandé pourquoi ce rapport était si courant ? S’agissait-il d’une sorte de connaissance secrète ou était-ce quelque chose de plus instinctif chez les directeurs de la photographie ?

John Seale a suggéré qu’il s’agissait probablement de la seconde solution en disant qu’il essayait simplement « de faire en sorte que le visage se sente bien dans le cadre ».

Murch a depuis recherché ce rapport dans de nombreux films (en analysant près de 800 images) et en est arrivé à l’idée que ce rapport est peut-être quelque chose d’inné en nous, parce qu’il se trouve tout autour de nous (et en nous), c’est peut-être pour cela que lorsque nous cadrons le visage, nous avons une sorte de « sensation » lorsqu’il est au bon endroit dans un cadre.

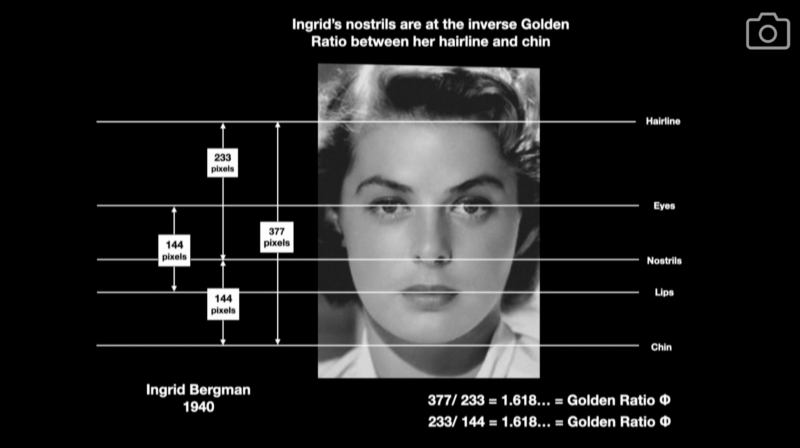

En poursuivant le séminaire, il a montré comment le visage humain lui-même est un « nid » de ratios d’or. Par exemple, la distance entre la racine des cheveux et le nez divisée par la distance entre le nez et le menton est un ratio d’or. Vous avez donc un visage (constitué de ratios d’or) encadré par un autre ratio d’or sur l’écran.

Images tirées de la Keynote de Walter Murch.

Pour expliquer ce phénomène, Murch propose une autre idée : « Peut-être l’écran est-il en fait un visage qui regarde le public ? »

Bien sûr, il ne s’agit pas de proposer une règle mais plutôt d’étudier une sorte de cadrage naturel ou « neutre » du visage.

Changer ce ratio peut créer des sentiments différents dans le public – placer les yeux au-dessus de la ligne du Nombre d’Or peut donner l’impression qu’un personnage est imposant ou menaçant, tandis que placer les yeux en dessous de la ligne peut donner l’impression qu’un personnage est faible. Il ne s’agit pas d’une formule, mais d’un élément dont il faut être conscient, avec lequel il faut jouer, ou d’un outil que nous pouvons utiliser en tant que cinéastes.

Il a bien sûr mentionné qu’il existe des contre-exemples de cette théorie qui sont également très réussis, notamment « Ida » (du réalisateur Paweł Pawlikowski et des directeurs de la photographie : Łukasz Żal et Ryszard Lenczewski).

Murch va poursuivre ses recherches et explorer d’autres aspects de sa théorie du Nombre d’Or (comme la comparaison avec la règle des tiers) en vue de son prochain livre. Bien qu’il n’ait pas donné d’indication quant à la date de sortie de son livre, gardez un œil sur celui-ci, car il nous donnera certainement d’autres sujets de réflexion, de discussion ou de débat dans le cadre de nos efforts continus pour devenir des créateurs d’images plus maîtrisées.

____

Walter Murch and the Golden Ratio in Cinematic Framing

One of the first seminars of this year’s Camerimage Fest comes from legendary editor Walter Murch – The Godfather (1972), The Conversation (1974), Apocalypse Now (1979), and many others – who shared his reflections on the Golden Ratio in cinematic framing. An intriguing theory about how DOPs and camera operators « naturally » tend to favor a similar position of a face in the frame.

One night while watching TV with his wife, Murch decided to try an experiment. So he grabbed some yarn from his wife (who was knitting at the moment) and taped the string horizontally on the screen at eye level. As they continued to watch, he noticed that the eyelines consistently fell into the same screen area. So being a somewhat mathematical person, he decided to take out a tape measure and measure the distance from the bottom of the screen to the yarn and then from the thread to the top of the screen. Then when he divided these numbers, the result was a ratio that he recognized as the Golden Ratio (1.618 or phi « ϕ »).

The Golden Ratio appears all around us in nature, from the spirals found in seashells, to the shapes of galaxies, even to the spiral of our own DNA. Intrigued, he began to wonder if this golden eye-line ratio appeared in other films and why he didn’t notice it after almost sixty years of editing films. So he put together a video of numerous film stills showing this relationship and spoke about it to Francis Ford Coppola and many of his cinematographer friends (including Vittorio Storaro and John Seale). He asked them why this ratio was so common. Was this some secret knowledge, or was it more instinctual among DOPs? John Seale suggested it’s probably the latter by saying he’s simply « trying to make the face feel comfortable within the frame. »

Murch has since looked for this ratio in numerous films (analyzing nearly 800 images) and has come to the idea that maybe this ratio is innate in us because it’s found all around (and within) us.

Perhaps that’s why when we frame the face; we have a sort of « feeling » when it’s in the right place of a frame. As he continued the seminar, he demonstrated how the human face itself is a « nest » of golden ratios. For example, the distance from the hairline to the nose divided by the distance from the nose to the chin is a golden ratio. So you have a face (a « nest » of golden ratios) framed within another gold ratio on the screen. To explain why this might be, Murch proposes another idea: « perhaps the screen is actually a face that looks back at the audience. »

Of course, this is not to propose a rule but to investigate a kind of natural or « neutral » framing of the face. Changing this ratio can create different feelings among the audience – putting the eyes above the golden ratio line might make a character feel imposing or threatening, while putting the eyes below the line might make a character feel weak. It’s not a formula but something to be aware of, something to play with, or a tool we can use as filmmakers. He mentioned, of course, that other counter-examples of this theory are also very successful, notably « Ida » (by director Paweł Pawlikowski and cinematographers: Łukasz Żal and Ryszard Lenczewski).

Mr. Murch will continue his research and explore other aspects of his golden ratio theory (like how it compares to the rule of thirds) in preparation for his next book. Although he didn’t hint at when it might be released, keep an eye out for it, as it’s sure to give us more to consider, discuss, or debate about in our continuing effort to become more masterful image-makers.

-

Partager l'article